“Black Beauty,” a nearly complete T. rex fossil in the Tyrrell musuem. The skeleton was stained black by magnesium. The skull in the foreground is the real one, but it was too heavy to mount so the display’s skull is a replica. Photo by me.

I recently visited the Royal Tyrrell Museum — a world-class natural history museum located in a tiny town called Drumheller in eastern Alberta. Alberta is incredibly rich with fossil history, and discoveries there give us a really comprehensive look at the history of life on Earth. This museum does a fantastic job of not only showcasing the amazing fossils themselves, but also providing crucial context for understanding why these fossils matter and what they tell us about our past. Visiting this museum really rekindled my fascination with natural history and prehistoric life.

Many displays focus on the Cretaceous period (the final piece of the age of dinosaurs before they went extinct) because Drumheller sits in the middle of windswept badlands that yield a veritable treasure trove of Cretaceous fossils — really classic dinosaurs like T. rex, hadrosaurs, and lots of ceratopsians. My favorite was the Boreopelta markmitchelli, an ankylosaur (armored dinosaur) so exquisitely preserved that it seemed to be taking a nap. I genuinely teared up looking at it. Dinosaur bones are one thing, but this specimen hit me hard with a “this was a real animal” epiphany.

Seeing this armored dinosaur in the flesh (the actual preserved skin!) was deeply moving. Photo by me.

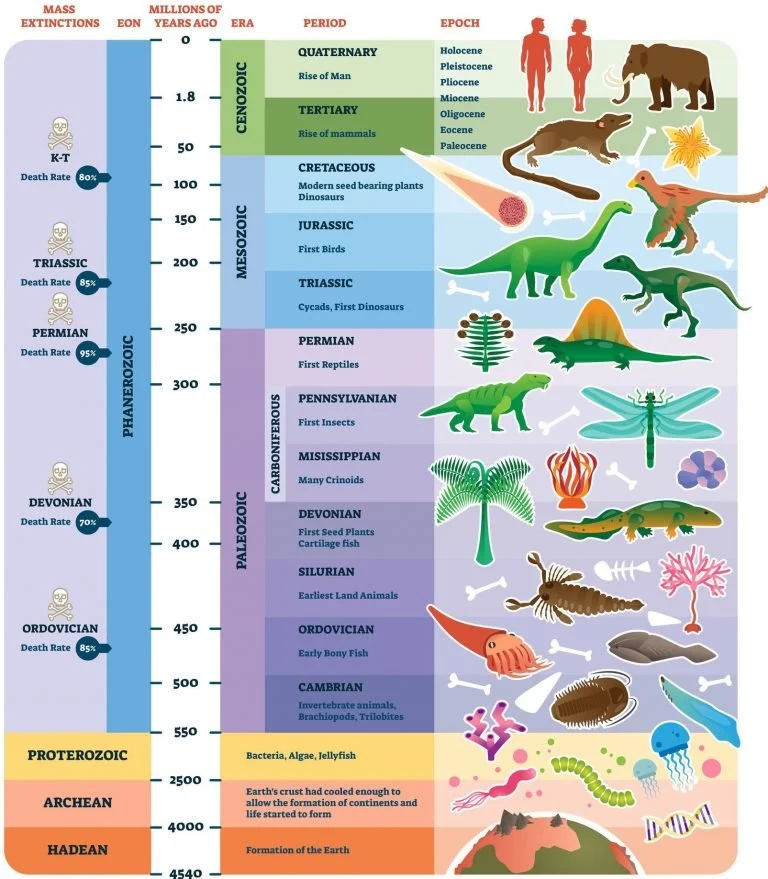

The dinosaurs in this museum are all amazing — but there’s a whole lot more to prehistoric life than dinosaurs. The museum had a path to follow where you walked through the different eras of Earth’s history — sections of time that scientists have divided out based on things like changes to geology, the environment, changes to dominant life forms, and mass extinction events. The first major stop along this path was the Cambrian period, and that’s what I want to talk about today.

You may have heard the term “Cambrian explosion” — what that refers to is a major change in the fossil record, where scientists see a huge expansion in the variety of life forms over the course of 13-25 million years. That sounds like a long time to us, but in geologic and evolutionary time? That’s fast — especially for the sheer scale and magnitude of change happening in this time. The result of all this diversification is that, by about 500 million years ago, we suddenly have the ancestors of every group of living animals today (plus a whole bunch of others that aren’t around anymore) all just swimming or crawling around in the ancient oceans.

This timeline is not to scale; the time since the Cambrian explosion is less than an eighth of Earth’s history. Image by normaals via Australian Environmental Education

And boy, are they weird. I’ve heard people describe the Cambrian explosion as “Mother Nature throwing spaghetti at the wall to see what sticks,” and yeah, that’s pretty accurate. These creatures evolved to fill certain roles in their ecosystem — predators, primary producers, scavengers, etc. — but in ways that seem totally alien to us. Here are a few of my favorite weirdos from this time.

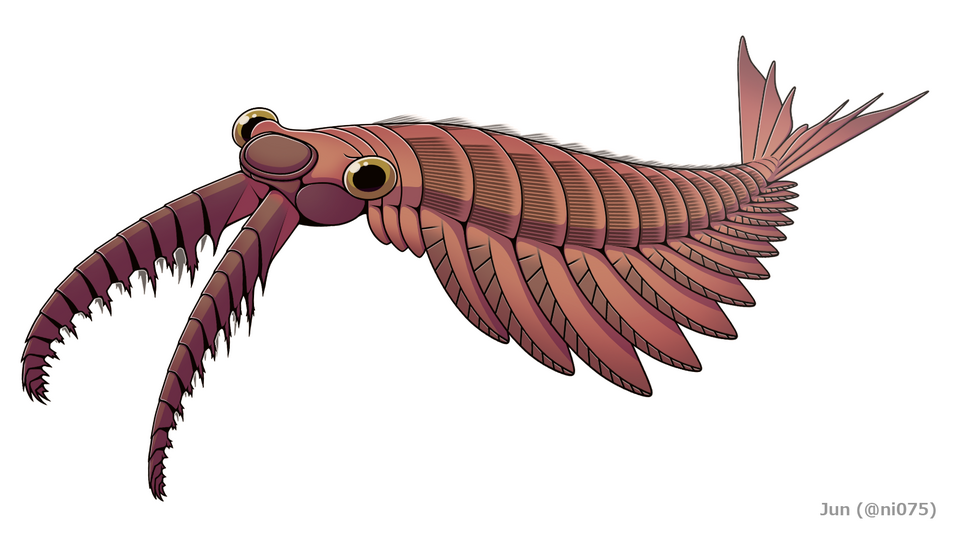

Anomalocaris. Image by Junnn11 via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Opabinia. Image by Qohelet12 via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Some of the best known Cambrian critters are early arthropods — animals with exoskeletons and usually lots of legs. Modern arthropods include insects, spiders, crabs, centipedes, isopods, etc. Back in the Cambrian, though, there were things like the mini-dachshund-sized anomalacaris, arguably the world’s first apex predator, and the weird-even-for-the-Cambrian opabinia, with five eyes and a single grabby extendo-mouth. These animals might have hunted the first trilobites, a massive group that thrived throughout the entire Paleozoic era (a span of about 290 million years).

Hallucigenia, or at least our current understanding of it. Image by Joshua Evans/Scorpion451 via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0)

The enigmatic hallucigenia was probably also some kind of arthropod, but one that’s more toward the edge of the family tree, kind of like how tardigrades (water bears) are a sister group to modern arthropods. (Incidentally, tardigrades also first appeared in the Cambrian). But it’s been a long road to figuring out hallucigenia’s deal. At first, scientists weren’t even sure of which side of the animal was up or which end was the front! Current thinking is that it walked on flexible, tube-like legs with the longer spines pointing up.

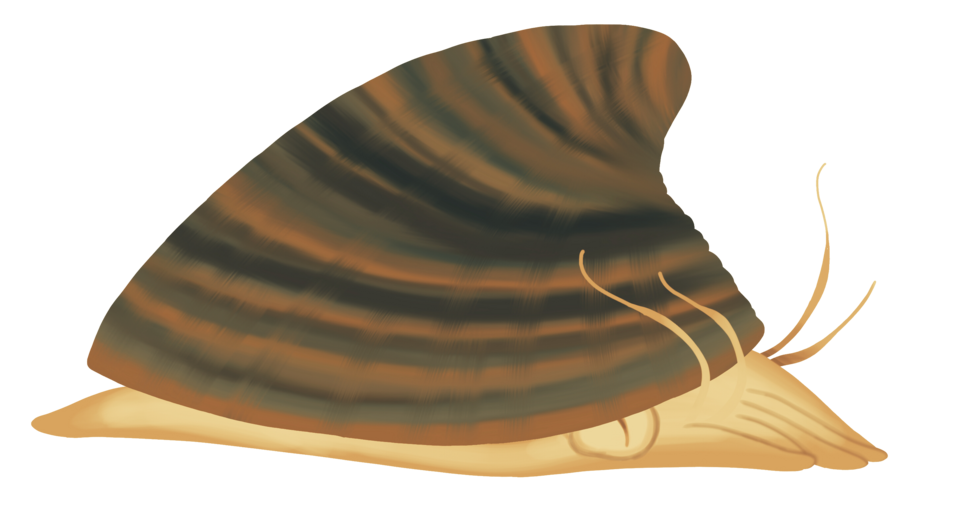

Wiwaxia. Image by Apokryltaros via Wikimedia Commons (GFDL)

Mollusks — the group that includes octopuses, snails, and clams — also first appeared in the Cambrian. One of the earliest we’ve found was the rather squashed-looking knightoconus. I have a particular fondness for plectronoceras, the first known animal to be definitively a cephalopod. I’ve made it clear just how much I love cephs, so this wizard-looking squid (or “squizard,” if you will) has a special place in my heart. The spiky but inexplicably adorable wiwaxia is another critter that we didn’t quite know how to place (kind of like hallucigenia), but for now it’s been tentatively grouped with the mollusks, as it had a muscular “foot” structure on the underside, similar to that of a snail.

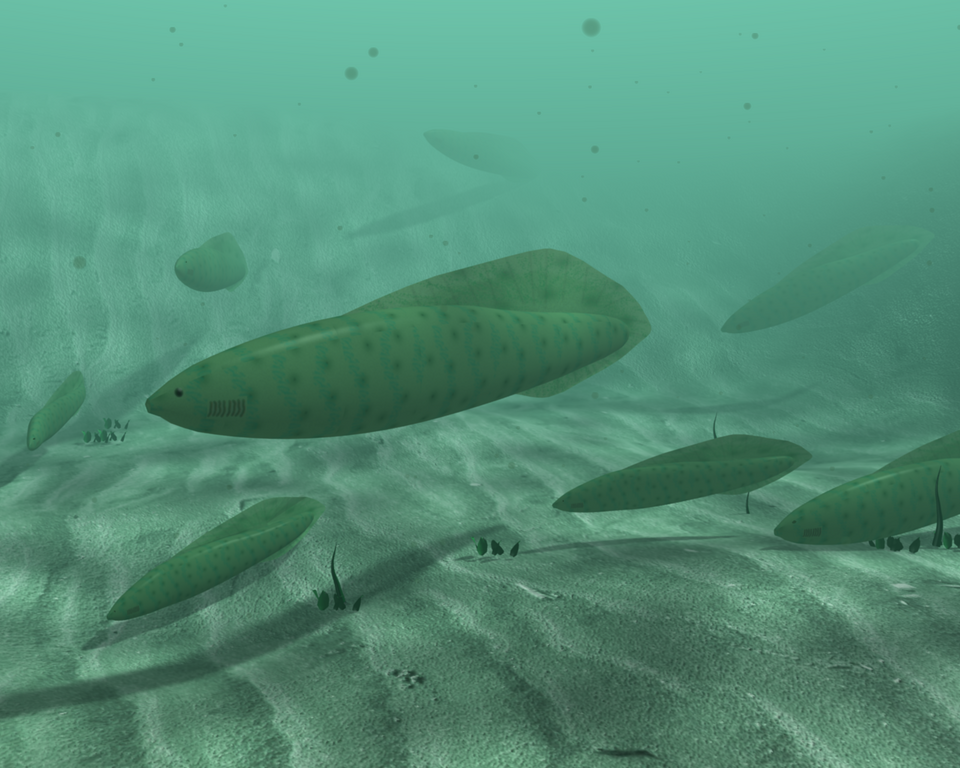

Finally, we have some creatures that stand out because of how unusually ordinary they look — a bit of an outlier in the Cambrian period. Pikaia and haikouichthys might look a bit boring next to anomalacaris and wiwaxia, but they had something special: the precursor to the spinal cord and central nervous system. These animals are some of the ancient ancestors of all vertebrates — including us humans! Haikouichthys in particular had a distinct head and gill arches: structures that would eventually evolve into jaws some 50 million years later.

Pikaia fossil. Image by Mussini et. al., via NYT

Haikouichthys. Image by Talifero via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)

How do we know about all of these guys? Fossils, of course — a lot of which come from the Canadian Rockies along the border of (you guessed it) Alberta and British Columbia. The Burgess Shale deposit in BC’s Yoho and Kootenay National Parks is one of the richest sources of Cambrian fossils in the world, and the discoveries made there have given us huge swathes of information about this strange, dynamic turning point in our planet’s history.

A trilobite fossil in the Burgess Shale. Image by Edna Winti via Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

Yeah, dinosaurs are cool, and the Tyrrell Museum does an excellent job of showing them to us and helping us learn about them. But let’s not forget all the weird little guys that kicked off all modern, complex life, hundreds of millions of years before the dinosaurs even thought about existing. (Plus all the other stuff in between, but that’s for another post.)