Photo by Simon Kutcher, via Wikimedia

Many years ago, I read Lewis and Clark’s account of their cross-continental voyage. My favorite part was the wide variety of spellings of “musquetors,” which were often “verry troublesome.” Lewis and Clark may have had spelling issues, but they were spot on in their “troublesome” description… mostly.

Mosquitoes have a bad reputation, and it’s not undeserved. They’re widely considered to be the deadliest animal on the planet, due to the diseases they spread — malaria, zika, dengue, yellow fever, and more. And even when they’re not spreading disease, they’re just plain annoying. But as unpleasant as they are, things would probably be a whole lot worse without them.

Mosquitoes lay eggs in standing water. Photo from TPPM Cairns.

Mosquitoes are insects of the diptera (flies) order. They’re incredibly widespread, increasingly so as the planet gets warmer, and they come in over 3,500 different varieties that thrive in all kinds of environments. Frozen polar regions are about the only place they can’t live, though they’re definitely more populous in warmer, wetter places. They need plants for nutrients, standing water for laying eggs, and not much else. And they reproduce fast, since their entire life lasts a week to a month.

If they just ate plant bits, mosquitoes wouldn’t be so much of an issue. But the females need protein from blood for their developing eggs, and that’s the “troubelsome” part, as Lewis and Clark might say. Not only is her bite annoying, but if she bites someone with bloodborne disease, she can pass that disease on to her next victim. When she bites, she pokes her needle-like structures through the skin, often painlessly. (In fact, medical engineers have developed new needles for vaccines based on mosquito mouthparts.) Her saliva is an anticoagulant that lets the blood keep flowing — and later, your body has an itchy allergic reaction.

Females have needle-like mouthparts for sucking the blood they need for producing eggs. Image by Dr. M. Baranitharan M.Sc Ph.D

New needles for vaccines. Image from NewScientist

This is all pretty unpleasant, so why put up with it? We humans are excellent at wiping out species — so how about we target mosquitoes? The thing is, eliminating mosquitoes (a) would be incredibly difficult if not downright impossible, and (b) isn’t as good of an idea as it might seem at first. Here’s a few reasons why.

Purple martins are among the many animals that eat mosquitoes. Photo from Animalia

Mosquitoes pollinate the blunt-leafed orchid. Photo from Native Orchids of the Pacific Northwest

Mosquitoes are a crucial part of many food webs. Tons of animals eat mosquitoes, and the mosquitoes themselves can eat quite a lot too. Food webs are a lot more complicated than biology textbooks show, and removing one part of it can have dramatic ripple effects across entire ecosystems.

Mosquitoes can help protect biodiversity and delicate wetland ecosystems by being… well, pests! They’ve kept large animals out of swamps, rainforests, and other delicate ecosystems for millions of years.

Mosquitoes drive wildlife migrations, particularly in arctic regions. Caribou herds keep moving — and therefore, don’t stay in one place and trash it — because mosquitoes drive them along.

Mosquitoes are pollinators. Both males and females feed on plant nectar. Just like bees, they move pollen around and help the plants reproduce.

Mosquitoes help control algae blooms. Larvae hatch in their pools of water, and chow down on plant particles floating alongside them.

So where does all of this information lead us? Mosquitoes are both important and harmful; this isn’t a black-and-white situation. We can (and should!) reduce mosquito numbers, especially in densely populated places, and we should certainly work on reducing or eliminating the diseases they spread. But we can do those things without going scorched earth on all mosquitoes.

These are some of the ways that people are approaching the problem:

Sleeping nets are common in parts of the world where malaria and other mosquito-borne diseases are widespread.

Mosquitoes need standing water to reproduce, so if you remove that water or relocate away from it, that can cut down on bites.

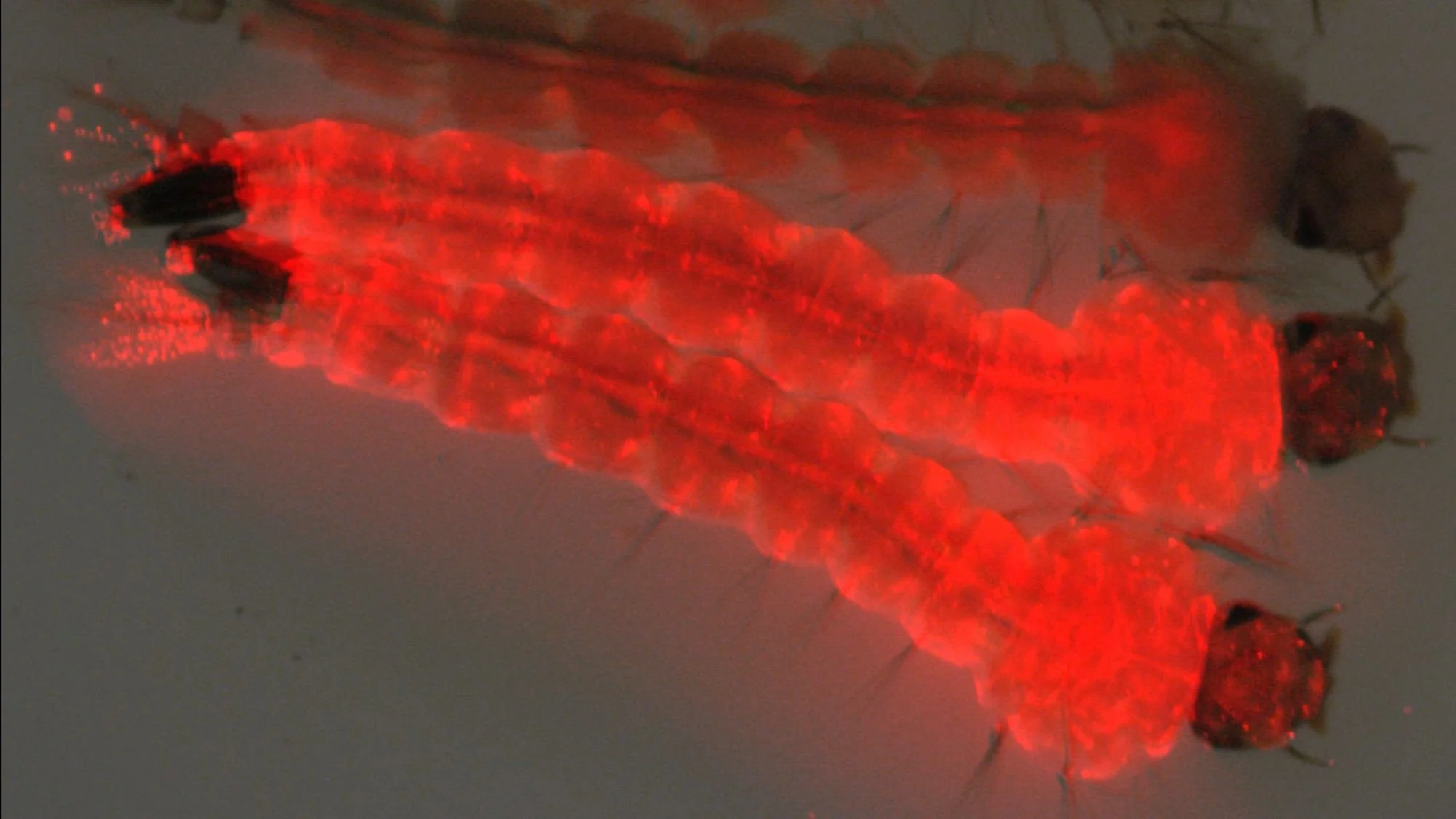

Genetically modified male mosquitoes will mate normally with females, but they pass on genes that kill the female offspring before they reach adulthood. In places where scientists have released these modified males, mosquito populations have dropped dramatically.

UMD scientists created a fungal infection that acts as a sort of “STD” for mosquitoes. Infected bugs mostly live out normal lives, but the infection kills them before the malaria parasite fully develops.

We can now vaccinate against malaria, and more vaccines are in development for diseases like zika, chikungunya, and dengue.

Genetically modified mosquito larvae glow red, so scientists can tell them apart from normal mosquitoes. Image by Oxitec, via CNN

The key to all of these solutions is education about mosquitoes, i.e. what I’m trying to do with this post. Doing this research has left me with a new — well, not appreciation, exactly, but let’s say — respect for those “verry troublesome musquetors.” And I hope it does for you too.